Even though it is now May – the heavy snowfalls in the New England states this past winter have left many with concerns. Here is an actual conversation, between a client who recently invested in a new Hansen Pole Building kit package, and our Technical Support Department:

Client: “Good Afternoon,

Quick couple of questions. The plans look like the wall girts for this project are the “commercial wall girt” design (Option 1)?

I was initially under the impression that Option 1 was just for the design where the “Roof Purlins /joist are hung vertically from the side of the Trusses”. I did not know that Option 1 also included a commercial wall girt design.

Is it necessary to use the commercial wall girt design if I have Option 1: “Roof Purlins /joist are hung vertically from the side of the Trusses” design? OR could the Wall Girts be just 2 x 4s nailed on the outside of the Support Posts?

Just curious-

After answering these couple of questions, I will log back in and approve the drawings.”

No snow yet, but we will get to it. Here is the response:

No snow yet, but we will get to it. Here is the response:

Thank you very much for your investment in a new Hansen Pole Building. Every building we provide has each member and connection structurally checked for adequacy under the most stringent Code provisions. Other than for very small column spacing, this means wall girts will need to be placed “book shelf” style, in order to be Code conforming.

Here is some reading which may prove helpful: https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/blog/2012/03/girts/

Now we will get literally knee deep into the snow:

“The structural support poles on my drawing are at 14 ft. Not 10 ft, and not 8 ft. This is my concern. (I read the guru blog). 14 feet between poles with double trusses, still doesn’t cut it when I could have 5 feet of snow on the roof. This barn will be located in Northern Maine.”

Thank you for your concerns. Your building has been designed for the loading recommended for your area, 50 psf ground snow load – which you acknowledged as being verified by you as adequate with your Building Department, prior to your order being placed.

If you are planning upon having five feet of snow sit on top of your roof, then we would recommend increasing the snow load capacity of your roof to somewhere in the vicinity of 100 psf (this would equate to a ground snow load of approximately 173 psf). To increase the roof snow load by this 346% would add $xxxx to your investment.

Please advise accordingly.

“After some further research, I have found that the recommended ground snow load for my county in Maine is 90 PSF. Please advise on new plan design and associated incremental cost to my project to accommodate.”

Just want to confirm you feel this will be adequate for your particular site, as a 90 psf ground snow load will support about 30-32″ of snow on the roof. If indeed you believe a greater depth may be placed upon it, it would behoove to design accordingly.

“The liability I am putting on myself here is tremendous. Does Hansen Pole Barns have any culpability for designing this building for snow load correctly? Because I don’t know. I am at a loss, I am not an engineer. We have little if any Code Enforcement in this county. But I know we get a boat load of heavy wet snow and the building will be in a sheltered area with not much winter sunlight.

My builder originally said it was 50 PSF (As he thought that was the code). But I don’t think knows. When I looked at the design that I was sent, (and I am a believer in engineering, as I am a non-certified Mechanical Engineer), I know the design is not adequate. So, I started to research on the internet. The best I can come up with is what I found on the internet. SEE ATTACHED

I am located in New Vineyard ME, Franklin County 04956. Every town that is near me shown on the attached “Ground Snow Loading” document is listed as “Case Study”, so I am guessing at the 90 PSF. (because everything around me is either at 90 or 100 PSF

Looking for advice”

Although you may have read this previously, it may prove good background: https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/blog/2012/02/snow-loads/

Based upon your information, we’d recommend a change in the Ce factor from 1.0 to 1.2. This effectively increases the design roof snow load by 20%

Along with this, here are some Pg options (in psf) to pick from (as well as the investment to increase) and the approximate depth of snow on the roof for each:

90 $ 2252 38″

100 2498 42″

110 2578 46″

120 3169 50″

130 3368 54″

Me personally, I tend to go for over design – I prefer to be the one who owns the last building standing when the storm of the century hits.

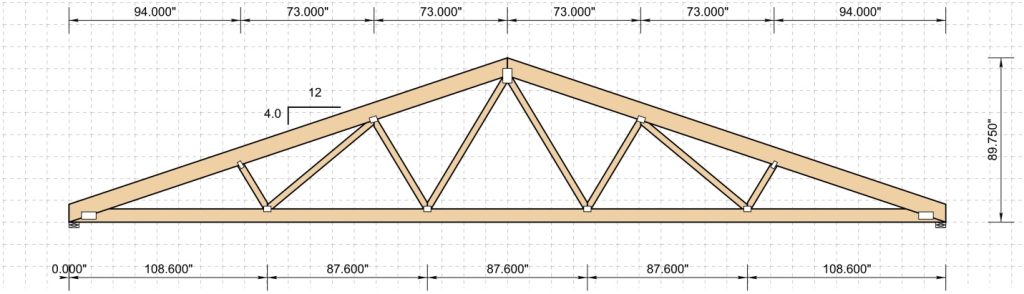

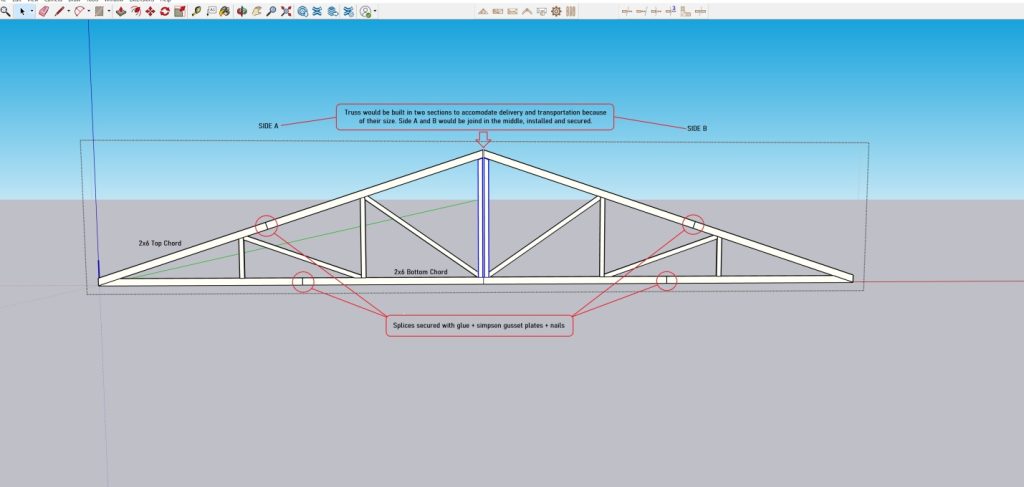

I spent two decades in management or owning prefabricated metal connector plated wood truss plants. In my humble opinion – attempting to fabricate your own trusses of this magnitude is a foolhardy endeavor, for a plethora of reasons:

I spent two decades in management or owning prefabricated metal connector plated wood truss plants. In my humble opinion – attempting to fabricate your own trusses of this magnitude is a foolhardy endeavor, for a plethora of reasons: Contractors generally have no qualms about using leftover materials from prior jobs, or purchasing cheaper materials than specified. If you seriously are concerned about material quality, take control yourself. Be aware, when contractors purchase materials for your building, they will mark them up. Paying for materials yourself assures you of not having liens against your property for bills your contractor did not pay.

Contractors generally have no qualms about using leftover materials from prior jobs, or purchasing cheaper materials than specified. If you seriously are concerned about material quality, take control yourself. Be aware, when contractors purchase materials for your building, they will mark them up. Paying for materials yourself assures you of not having liens against your property for bills your contractor did not pay. Hiring a contractor? Then, standards for workmanship should be clearly specified. For post-frame buildings this would be Construction Tolerance Standards for Post-Frame Buildings (ASAE Paper 984002) and Metal Panel and Trim Installation Tolerances (ASAE Paper 054117). Depending upon scope of work, other standards may apply such as ACI (American Concrete Institute) 318, ACI Concrete Manual and APA guidelines (American Plywood Association).

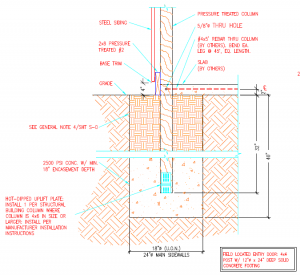

Hiring a contractor? Then, standards for workmanship should be clearly specified. For post-frame buildings this would be Construction Tolerance Standards for Post-Frame Buildings (ASAE Paper 984002) and Metal Panel and Trim Installation Tolerances (ASAE Paper 054117). Depending upon scope of work, other standards may apply such as ACI (American Concrete Institute) 318, ACI Concrete Manual and APA guidelines (American Plywood Association). Sigh…..without an adequate footing beneath columns your building is going to sink. A minimum 6″ thick concrete footing needs to be poured under every column. There should also be a provision to prevent uplift. I would recommend no further payments to them until this issue is resolved. They should be providing an engineer certified solution to this.

Sigh…..without an adequate footing beneath columns your building is going to sink. A minimum 6″ thick concrete footing needs to be poured under every column. There should also be a provision to prevent uplift. I would recommend no further payments to them until this issue is resolved. They should be providing an engineer certified solution to this. Wikipedia may consider a lean-to a simple structure, however there is far more involved than may meet the eye. Before diving deep into adding a lean-to to an existing pole barn (post frame building) a competent Registered Design Professional (RDP – engineer or architect) should be engaged to determine the adequacy of the existing structure to support the lean-to. Failure to do so can result in catastrophic failures – causing injury or death.

Wikipedia may consider a lean-to a simple structure, however there is far more involved than may meet the eye. Before diving deep into adding a lean-to to an existing pole barn (post frame building) a competent Registered Design Professional (RDP – engineer or architect) should be engaged to determine the adequacy of the existing structure to support the lean-to. Failure to do so can result in catastrophic failures – causing injury or death.

No snow yet, but we will get to it. Here is the response:

No snow yet, but we will get to it. Here is the response: The owners of The Castle Rock Inn chose a pole building to replace the structure, saving months of time by not having to wait for spring in order to excavate and pour the continuous footings and foundations which would have been needed in other forms of construction. While the pole building was sadly not provided by Hansen Pole Buildings, Rick stopped by to take some photos of the new construction. Among the photos might be one of the saddest examples of a retaining wall which I have witnessed.

The owners of The Castle Rock Inn chose a pole building to replace the structure, saving months of time by not having to wait for spring in order to excavate and pour the continuous footings and foundations which would have been needed in other forms of construction. While the pole building was sadly not provided by Hansen Pole Buildings, Rick stopped by to take some photos of the new construction. Among the photos might be one of the saddest examples of a retaining wall which I have witnessed. One of our clients had been discussing with Hansen Pole Buildings Designer Lily a pole building to be located in rural Larimer County. The county had provided him with a sheet of “prescriptive” requirements for non-commercial, non-residential pole barns in the county.

One of our clients had been discussing with Hansen Pole Buildings Designer Lily a pole building to be located in rural Larimer County. The county had provided him with a sheet of “prescriptive” requirements for non-commercial, non-residential pole barns in the county. When a pole building is constructed from engineered plans (not just the use of prefabricated metal connector plated trusses, built from engineer sealed truss drawings), oftentimes the Registered Design Professional (RDP – engineer or architect) can provide a brief letter to the Building Official, in the event things have gone astray. Sometimes a sketch needs to also be provided, but (provided this method is acceptable to the Building Official) this fix is going to prove far less expensive than having to rework one or more pages of the blueprints.

When a pole building is constructed from engineered plans (not just the use of prefabricated metal connector plated trusses, built from engineer sealed truss drawings), oftentimes the Registered Design Professional (RDP – engineer or architect) can provide a brief letter to the Building Official, in the event things have gone astray. Sometimes a sketch needs to also be provided, but (provided this method is acceptable to the Building Official) this fix is going to prove far less expensive than having to rework one or more pages of the blueprints.

If he wasn’t a building official, it wouldn’t really matter much whether he gets rankled or not. If he was a supplier or subcontractor, fine, take the risk; if he can’t handle it, hire a new one. But you can’t hire new building officials. Get on the wrong side with one and run the risk of installing yourself on the person’s or jurisdiction’s blacklist. Navigating the regulatory quagmire is hard enough without painting a sign on your forehead which says “I am a jerk.”

Trust me on this one – getting into the jerk line at the Building Department is tantamount to waterboarding. Life…will….become….miserable.

I have heard of projects where during construction the engineer of record got calls from the contractor asking for interpretations to the cryptic red marks all over the structural plans. This is alarming because engineers do not release construction plans with red marks on them. If corrections are to be made, engineers make them in the office and reissue the plans. What has happened is an overzealous plans examiner took it upon himself to change the engineered plans via red marks and then issue the plans for construction without bothering to ask or tell the engineer!

In changing the engineer’s design, the Building Department superseded the actual registered engineer as the engineer of record and assumed all sorts of liability. If their risk manager ever got wind of this, heads would roll. And roll they should.

Oftentimes, engineers do nothing about this, especially if it is near an Act of Congress to obtain a building permit in the particular jurisdiction. Sadly sometimes the only way to obtain a permit is via the building department redoing the design and assuming the liability. Raising a stink could cause long delays in the issuance of a permit.

Before questioning the Building Official, weigh the costs. If the building inspector is a reasonable person, ask the question. If, on the other hand, the inspector is seemingly “out to get you”, maybe let the issue pass and then at the end of the project bring it up to his superior.

If you are a Building Official and reading this, please do give me feedback on “smoothing the road”. Trust me; I am on your side. My goal is always the same: To provide adequate support and education to clients to assist them in getting a well-designed pole building which is safe, sound…and built to code.

If he wasn’t a building official, it wouldn’t really matter much whether he gets rankled or not. If he was a supplier or subcontractor, fine, take the risk; if he can’t handle it, hire a new one. But you can’t hire new building officials. Get on the wrong side with one and run the risk of installing yourself on the person’s or jurisdiction’s blacklist. Navigating the regulatory quagmire is hard enough without painting a sign on your forehead which says “I am a jerk.”

Trust me on this one – getting into the jerk line at the Building Department is tantamount to waterboarding. Life…will….become….miserable.

I have heard of projects where during construction the engineer of record got calls from the contractor asking for interpretations to the cryptic red marks all over the structural plans. This is alarming because engineers do not release construction plans with red marks on them. If corrections are to be made, engineers make them in the office and reissue the plans. What has happened is an overzealous plans examiner took it upon himself to change the engineered plans via red marks and then issue the plans for construction without bothering to ask or tell the engineer!

In changing the engineer’s design, the Building Department superseded the actual registered engineer as the engineer of record and assumed all sorts of liability. If their risk manager ever got wind of this, heads would roll. And roll they should.

Oftentimes, engineers do nothing about this, especially if it is near an Act of Congress to obtain a building permit in the particular jurisdiction. Sadly sometimes the only way to obtain a permit is via the building department redoing the design and assuming the liability. Raising a stink could cause long delays in the issuance of a permit.

Before questioning the Building Official, weigh the costs. If the building inspector is a reasonable person, ask the question. If, on the other hand, the inspector is seemingly “out to get you”, maybe let the issue pass and then at the end of the project bring it up to his superior.

If you are a Building Official and reading this, please do give me feedback on “smoothing the road”. Trust me; I am on your side. My goal is always the same: To provide adequate support and education to clients to assist them in getting a well-designed pole building which is safe, sound…and built to code.  There is just no possible way for any one person to know all of this information, and how it applies.

There is just no possible way for any one person to know all of this information, and how it applies.