This week the Pole Barn Guru answers reader questions about column height for an eight foot one inch interior ceiling, what size bi-fold door for a hangar, and specific boards for a splash plank.

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: New at this. If I am building a pole barn house and want 8 ft 1 inch between slab and bottom of truss, have 4 inches of slab and 2 inches of Styro and need have top of footing at 42 inches, I come up with 145 inches. A 12 foot pole is 144. Can this work and pass code or do I need to go with a longer post.

Thanks for any help. BRADLEY in SHELBY

DEAR BRADLEY: My recommendation is for you to be building from a fully engineered set of building plans. When you are provided with a design frost depth from your Building Department, it is telling you the BOTTOM of the footing must be at or below the design frost depth.

DEAR BRADLEY: My recommendation is for you to be building from a fully engineered set of building plans. When you are provided with a design frost depth from your Building Department, it is telling you the BOTTOM of the footing must be at or below the design frost depth.

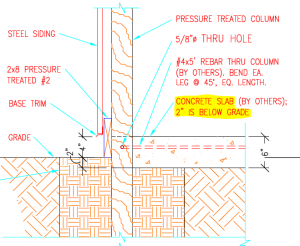

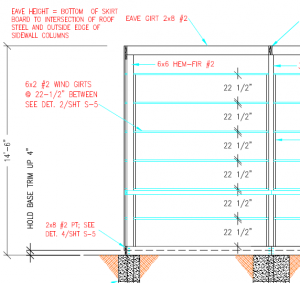

If this was a Hansen Pole Building, our engineers would specify column holes to be 42″ deep from grade. The bottom 8″ of this hole would be filled with concrete (below the column) as part of a monopoured bottom collar. Your building footprint would be lowered two inches below grade to allow for your sub-slab insulation. Top of a nominal four inch slab will be at 3-1/2″ above grade. Normally height from top of slab to bottom of trusses to give an eight foot finished ceiling would be 8′ 1-1/8″. One thing you have not accounted for is raised heel trusses to allow for full insulation thickness from outside of wall to outside of wall. In your area we would recommend R-60 attic insulation, with 22 inch high raised heel trusses. Given this information, your columns should be 14′.

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: I am contemplating building a hangar, planning at this point on a 60 x 60 hangar, and wondering what the maximum opening span would be with a bi-fold door. Thanks! KEVIN in BELLAIRE

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: I am contemplating building a hangar, planning at this point on a 60 x 60 hangar, and wondering what the maximum opening span would be with a bi-fold door. Thanks! KEVIN in BELLAIRE

DEAR KEVIN: On each side of the hangar door your building will need what is known as a ‘braced wall panel’ of solid wall. The width of this area is limited to a maximum ratio of panel width to building eave height of 1:3.5 (as an example on a 14′ eave building would be 4′).

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: What boards do I use for outside band for first floor > 20ft by 40ft -6×6 posted 10 on center. JOSEPH in CLINTON

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: What boards do I use for outside band for first floor > 20ft by 40ft -6×6 posted 10 on center. JOSEPH in CLINTON

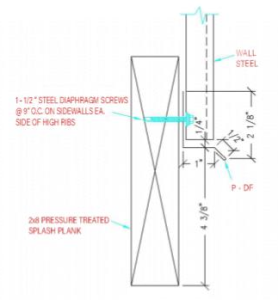

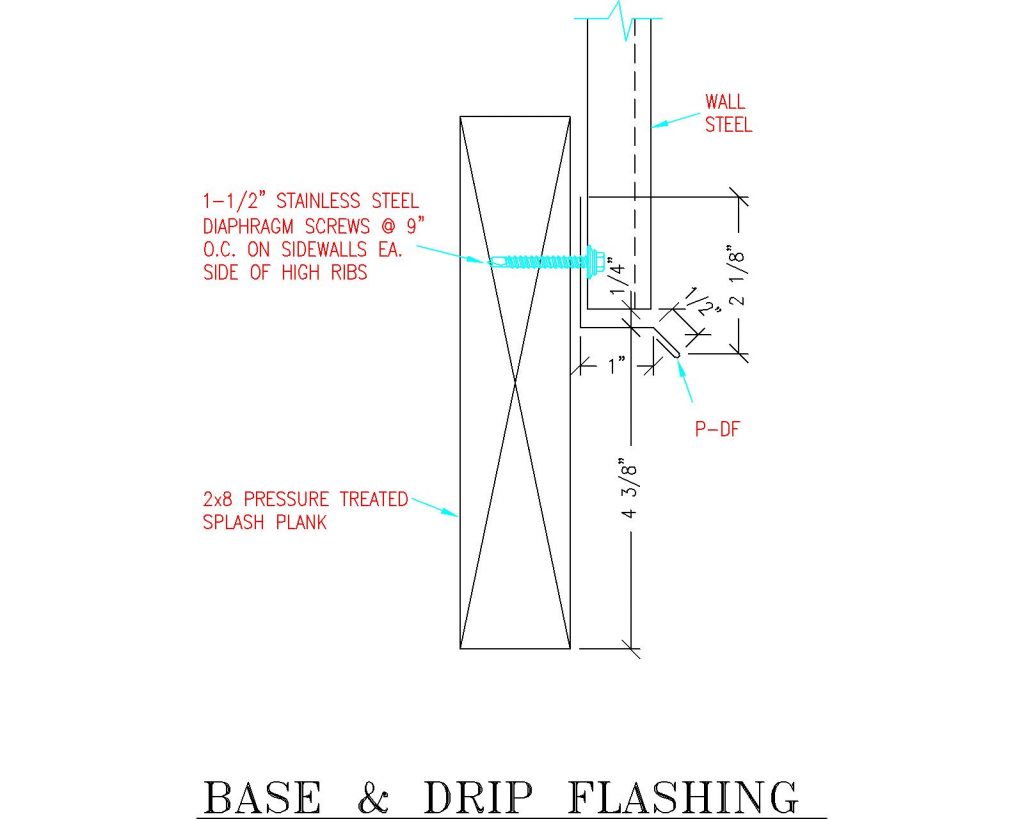

DEAR JOSEPH: First floors are at grade, so your ‘outside band’ would be called out for on your fully engineered building plans as being a pressure preservative treated splash plank of some dimension (in our case, with steel siding it will be a 2×8 treated to UC-4A or ground contact).

Thank you for your kind words. Certainly any building could be designed for door openings, ceiling heights, etc., to be adjusted for top of slab on grade to be at any point. This would entail leaving greater amounts of splash plank exposed on exterior beneath siding in order to prevent concrete aprons, sidewalks, driveways, etc., from being poured up against wall steel. Some people find great amounts of splash plank being exposed to be aesthetically unpleasant however. By being consistent in design, it also allows for one set of assembly instructions to be used – rather than having to rely upon making adjustments for whatever custom situation individuals (or their builders) deemed their particular case.

Thank you for your kind words. Certainly any building could be designed for door openings, ceiling heights, etc., to be adjusted for top of slab on grade to be at any point. This would entail leaving greater amounts of splash plank exposed on exterior beneath siding in order to prevent concrete aprons, sidewalks, driveways, etc., from being poured up against wall steel. Some people find great amounts of splash plank being exposed to be aesthetically unpleasant however. By being consistent in design, it also allows for one set of assembly instructions to be used – rather than having to rely upon making adjustments for whatever custom situation individuals (or their builders) deemed their particular case. DEAR

DEAR DEAR TOM: You’ll want to make certain your proposed 20′ x 30′ area will be adequate for all of your needs. You may find increasing building footprint to say 24′ x 36′ to not be significantly more expensive of an investment, whilst providing 44% more space. With every building we provide being a custom design to best fit client needs, we can certainly provide exactly what you are looking for. A Hansen Pole Buildings’ Designer will be in contact with you shortly.

DEAR TOM: You’ll want to make certain your proposed 20′ x 30′ area will be adequate for all of your needs. You may find increasing building footprint to say 24′ x 36′ to not be significantly more expensive of an investment, whilst providing 44% more space. With every building we provide being a custom design to best fit client needs, we can certainly provide exactly what you are looking for. A Hansen Pole Buildings’ Designer will be in contact with you shortly.

First, a question is hiding a building exterior pressure preservative treated skirt board (aka splash plank). Simple answer is yes, building is already designed so this can be done. Skirt board should be placed per engineer sealed building plans, showing drip edged base trim bottom four inches above grade. This allows for a nominal four inch thick (finished thickness 3-1/2”) sidewalk, driveway, landing or other concreted areas to be poured against exterior of splash plank, coming in ½ inch below bottom of drip edge. Any such pours should be along a grade sloping sufficiently away from building a minimum slope of 2%, to keep water from pooling against building.

First, a question is hiding a building exterior pressure preservative treated skirt board (aka splash plank). Simple answer is yes, building is already designed so this can be done. Skirt board should be placed per engineer sealed building plans, showing drip edged base trim bottom four inches above grade. This allows for a nominal four inch thick (finished thickness 3-1/2”) sidewalk, driveway, landing or other concreted areas to be poured against exterior of splash plank, coming in ½ inch below bottom of drip edge. Any such pours should be along a grade sloping sufficiently away from building a minimum slope of 2%, to keep water from pooling against building. DEAR POLE BARN GURU: The pole building garage at the house I bought has two skirt boards. Can I remove the interior board to remove the dirt easier and put quikrete in its place. There is a 5” gap between the wall and the floor. The previous owner started putting quikrete in some places. Looks like the floor was put in before the building was built. KENNY in PARKERSBURG

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: The pole building garage at the house I bought has two skirt boards. Can I remove the interior board to remove the dirt easier and put quikrete in its place. There is a 5” gap between the wall and the floor. The previous owner started putting quikrete in some places. Looks like the floor was put in before the building was built. KENNY in PARKERSBURG

DEAR KENNY: The Hansen Pole Buildings’ warehouse has the exact same situation. The interior splash plank is doing nothing for you or your building, feel free to remove it.

DEAR KENNY: The Hansen Pole Buildings’ warehouse has the exact same situation. The interior splash plank is doing nothing for you or your building, feel free to remove it. DEAR BILL: In short, yes – we can provide a building ready for you to side. What we most typically provide is 7/16” thick OSB over bookshelf girts 24 inches on center, with housewrap over the sheathing. If your false log siding can structurally provide resistance to shear, the OSB could be omitted, however this would not be my recommendation.

DEAR BILL: In short, yes – we can provide a building ready for you to side. What we most typically provide is 7/16” thick OSB over bookshelf girts 24 inches on center, with housewrap over the sheathing. If your false log siding can structurally provide resistance to shear, the OSB could be omitted, however this would not be my recommendation. DEAR POLE BARN GURU: Do you include foundation plans with your kits? JOE

DEAR POLE BARN GURU: Do you include foundation plans with your kits? JOE I hate it when this happens – basically the builder used the lower splash plank (aka skirt board) to screed the concrete off from then had to add the upper one in order to have something to attach the siding to. Now you are stuck with the challenge.

I hate it when this happens – basically the builder used the lower splash plank (aka skirt board) to screed the concrete off from then had to add the upper one in order to have something to attach the siding to. Now you are stuck with the challenge.

Known also as a Bottom Girt, Grade Girt, Skirt Board or Splash Plank, it is a decay and corrosion resistant girt which is in soil contact or located near the soil surface. It remains visible from the building exterior upon building completion, and is normally two inches in nominal thickness.

Known also as a Bottom Girt, Grade Girt, Skirt Board or Splash Plank, it is a decay and corrosion resistant girt which is in soil contact or located near the soil surface. It remains visible from the building exterior upon building completion, and is normally two inches in nominal thickness.