You Can Do It!

Screamed headlines of my first ever print display ad for pole barn kits in 1981!

I have included below a snippet from one of my first blog posts from 10 years ago:

“In the summer of 1979, home interest rates began to rise. Idaho had a usury limit, home mortgages stopped in Idaho. I set out looking for other opportunities and ended up in Salem, Oregon.

I was offered the position of truss plant manager at Lucas Plywood and Lumber, in August 1979. It would be a smooth transition, as the prior manager would be there for a month or so to ease me into the system. At first glance, the operation was frightening. I was used to trusses being manufactured using hydraulic presses to embed the steel plates into the trusses, not teams of workers banging them in with hammers and pushing them through a set of “rollers”. Even more frightening was when I discovered all the lumber being used was green (I had no idea trusses were built anywhere with lumber which was not kiln dried). But my total heart failure nearly occurred when I found they were using lumber graded as Standard and better for truss chords, as someone had convinced them it was the same as #2 and better. Not even close! Well, the previous plant manager packed up at noon of the first day saying, “Good luck, son”. My first several months were spent on educating the troops and introducing dry lumber, both with some successes. The lumber sales team was my age as well, which helped to gain eager learners. I taught them how to do lumber lists from building plans, so they could quote framing packages.

In January 1980, the housing crunch I had fled from in Idaho hit Oregon. My truss plant, which typically produced 8 to 10 buildings worth of trusses a day, had only four orders in the entire month! Not good – however there was a single common denominator among those four orders, they were all for pole barn trusses. I didn’t have the slightest idea what a pole barn was, but it was time to find out. I picked the brain of a long time pole barn builder, George Evanovich, who explained the basics to me.

Now I have to confess, I was brought up with, “Wood is good”, so the entire concept of using roll formed steel for roofing and siding was a novel experience for me. Having convinced myself it had its place, we figured out material prices for some fairly typical pole barns and ran ads selling building kits. The response was overwhelming. By April, we were not only running the truss plant full time again (producing primarily pole barn trusses), we had also hired George and his two crews to construct buildings for our clients. By June, the truss plant was operating double shifts, just to keep up with the volume.”

For those of you interested, the full text of this post can be found here: https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/2011/06/theres-no-education-like-real-life-business-experience/

Anyhow, back on point, there were an incredible number of people totally willing to undertake erection of their own pole barns. Even more amazing is – any of them turned out! We provided absolutely no instructions and “plans” (I use this term lightly) were drawn by hand on a few sheets of 8-1/2” x 11” white copy paper.

Anyhow, back on point, there were an incredible number of people totally willing to undertake erection of their own pole barns. Even more amazing is – any of them turned out! We provided absolutely no instructions and “plans” (I use this term lightly) were drawn by hand on a few sheets of 8-1/2” x 11” white copy paper.

Moving forward four decades in time, Hansen Pole Building kits have greatly evolved, and not just in quality, benefits and features – but in ease of assembly for an average D-I-Yer.

Your new Hansen Pole Buildings’ kit is designed for you (an average physically capable person, who can and will read and follow instructions), to successfully construct your own beautiful building shell (and most of our clients do DIY – saving tens of thousands of dollars). We’ve had clients ranging from septuagenarians to fathers bonding with their teenage daughters erect their own buildings, so chances are – you can as well!

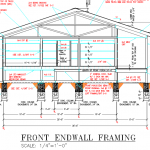

Your new building investment includes full multi-page 24” x 36” engineer sealed structural blueprints detailing locations and attachments of every piece (as well as suitable for obtaining Building Permits), the industry’s best, fully illustrated, step-by-step installation manual, and unlimited technical support from people who have actually built post frame buildings. Even better – it includes our industry leading Limited Lifetime Structural warranty!

Your new building investment includes full multi-page 24” x 36” engineer sealed structural blueprints detailing locations and attachments of every piece (as well as suitable for obtaining Building Permits), the industry’s best, fully illustrated, step-by-step installation manual, and unlimited technical support from people who have actually built post frame buildings. Even better – it includes our industry leading Limited Lifetime Structural warranty!

Yes – You CAN do it!