I’ve been blessed with being able to have extensive tours of two very sophisticated lumber mills. The first being the Seneca Sawmill in Eugene, Oregon.

Seneca Sawmill Company is one of the largest producing single-location sawmills in the United States. Their mills are capable of producing over 650 million board feet per year of premium grade green and dry Douglas-fir dimension lumber and studs, and dry Hem-fir studs. To give a perspective, this would be somewhere around 25 rail cars every week day! Seneca’s goal is to produce the best lumber available, while consuming less raw material than any other sawmill in the world. They pride ourselves in the fact they utilize virtually 100 percent of each log brought to their mills from their forestlands.

One of the things which impressed me was Seneca Sawmill’s use of equipment which allows them to “saw size” lumber, eliminating the need for planning! This saves time, equipment, operators and provides for more efficient recovery from the log being sawn.

Our home on Newman Lake, Washington has 26 foot long 2×14 lumber sawn at Seneca.

The lumber which goes into your new post frame building starts off as a tree in the forest

Several reality television programs appear to delve deeply into the world of logging and I would suggest a few views of Ax Men, Swamp Loggers, American Loggers or Extreme Loggers to cover the portion from tree to log on the lumber truck. Some might best be watched with a block of salt as they are, after all, dramas.

Once at the mill, giant mobile unloaders grab the entire truck load in one bite and stack it in long piles, known as log decks. The decks are periodically sprayed with water to prevent the wood from drying out and shrinking, or combusting.

Logs are picked up from the log deck and are placed on a chain conveyor which brings them into the mill. The outer bark of the log is removed, either with sharp-toothed grinding wheels or with a jet of high-pressure water, while the log is slowly rotated. The removed bark is pulverized and may be used as the mill’s furnace fuel or sold as mulch.

Logs are picked up from the log deck and are placed on a chain conveyor which brings them into the mill. The outer bark of the log is removed, either with sharp-toothed grinding wheels or with a jet of high-pressure water, while the log is slowly rotated. The removed bark is pulverized and may be used as the mill’s furnace fuel or sold as mulch.

Logs are tipped off the conveyor, parallel to the direction the saw will be cutting, and clamped onto a moveable carriage which slides lengthwise on a set of rails. The carriage can position the log in relationship to the saw and can also rotate it 90 or 180 degrees about its length. Optical sensors scan the log and determine its diameter at each end, its length, and any visible defects. Based on this information, a computer then calculates a suggested cutting pattern to maximize the number of pieces of lumber obtainable from the log. This is the exact process I viewed at Seneca Sawmill and I found it to be fascinating.

The pieces of lumber are then moved to an area to be dried, or “seasoned.” This is necessary to prevent decay and to permit the wood to naturally shrink as it dries out. Timbers, (5 inches by 5 inches and larger) because of their large dimensions, are difficult to thoroughly dry and are generally sold wet, or “green.” Dry lumber contains 19% or less moisture. Air-dried lumber is stacked in a covered area with spacers between each piece to allow air to circulate. Kiln-dried lumber is stacked in an enclosed area, while 110-180°F heated air is circulated through the stack.

Read more about the whys of dried lumber here: https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/2012/04/drying-wood/.

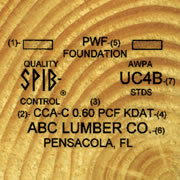

Each piece of lumber is visually or mechanically inspected and graded according to the amount of defects present. The grade is stamped on each piece, along with information about the moisture content, and a mill identification number. The lumber is then banded into units according to the type of wood, grade, and moisture content. Most dry lumber units are then wrapped and are then ready for shipping.

For more information on mechanically inspected lumber – https://www.hansenpolebuildings.com/2012/12/machine-graded-lumber/.